"Oh, she's from Africa."

"Um, okay," I said. "Which country?"

"Let's see. Benin. Yes, that was it, Benin."

Our conversation moved on from there, but it left me with the realization that I'd just witnessed another common white tendency: to think of people from countries in the continent of Africa as "Africans." Instead of as citizens of a particular country.

Why do we do this? In my experience, we rarely homogenize people from Asian countries in quite that same way. I can recall being told about many individuals from that continent by white people, who usually identify the specific country they're from. They say things like, "That's Lalana. She's from Thailand," instead of, "That's Lalana. She's from Asia."

And I really don't think I've ever heard anyone homogenize a person in continental terms from Europe this way, as in, "That's Jurgen. He's from Europe." Instead, we immediately tie that person's identity to their specific country, and not to an entire continent. Same thing, in my experience, for people whose countries are in South America -- I've heard things like "She's from Brazil" far more often than "She's from South America," which I can't recall ever hearing before. But then, in somewhat different geographical terms, I have encountered people in the U.S. who assume that Latinos, who could be from many different countries, are all "Mexican"; the term "Native American" can obscure specific tribal affiliations as well.

I suppose that other, non-white people in the U.S., and in the West more generally, homogenize in this way too -- when it comes to Africa, it's certainly a "First World" way of looking down, in a delusional manner, on the supposed "Third World." But when white Americans do it, unspoken (and even unconscious) presumptions of racial superiority can add weight to the problem.

What we're usually exhibiting when we refer to people as "Africans" is something that the Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie calls "the danger of a single story."

In a TED lecture that Adichie gave this past summer (video below), she describes the identity-crushing effects of European literature on her own efforts to write stories as a child. Because of her early encounters with that which had been labeled for her as "literature," and thus implicitly deemed "superior," her own stories were initially filled with white, blue-eyed characters.

Adichie then describes her arrival at a university in the U.S.:

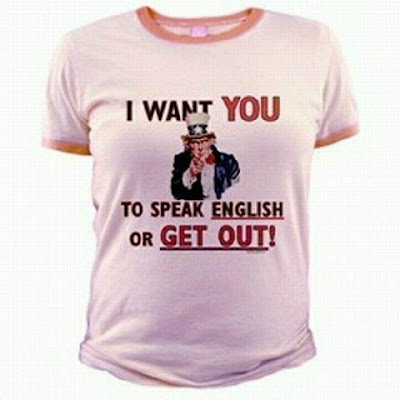

I was 19. My American roommate was shocked by me. She asked where I had learned to speak English so well, and was confused when I said that Nigeria happened to have English as its official language. She asked if she could listen to what she called my “tribal music,” and was consequently very disappointed when I produced my tape of Mariah Carey. She assumed that I did not know how to use a stove.

What struck me was this: She had felt sorry for me even before she saw me. Her default position toward me, as an African, was a kind of patronizing, well-meaning, pity. My roommate had a single story of Africa. A single story of catastrophe.

One thing that people in the U.S. don't seem to realize is how much racial and ethnocentric baggage they carry, and how much the contents of that baggage can spill out into such simple vehicles as their choice of particular words. Even single words, like "Africa," or "African." Part of that baggage is, as Adichie says, a presumptuous sense of superiority -- however unconscious that may be, it's there inside us. And unless we wake up and work to counter it, it's going to reveal itself in our words and actions. Also, as I said above, the baggage of this sort that white Westerners carry is even heavier, and that's because they've been raised in a de facto white supremacist context.

Would we feel better if we could somehow unload this ethnocentric baggage? Lighter, perhaps, and more free to move around, maybe toward other people, rather than away from them?

Adichie goes on to generously explain some problematic assumptions that a single word can express, and also how it feels as a Nigerian to be perceived instead as an "African":

In this single story there was no possibility of Africans being similar to [my roommate], in any way. No possibility of feelings more complex than pity. No possibility of a connection as human equals.

I must say that before I went to the U.S., I didn’t consciously identify as African. But in the U.S., whenever Africa came up people turned to me. Never mind that I knew nothing about places like Namibia.

But I did come to embrace this new identity, and in many ways I think of myself now as African. Although I still get quite irritable when Africa is referred to as a country. The most recent example being my otherwise wonderful flight from Lagos two days ago, in which there was an announcement on the Virgin flight about the charity work in “India, Africa and other countries.”

So after I had spent some years in the U.S. as an African, I began to understand my roommate’s response to me. If I had not grown up in Nigeria, and if all I knew about Africa were from popular images, I too would think that Africa was a place of beautiful landscapes, beautiful animals, and incomprehensible people, fighting senseless wars, dying of poverty and AIDS, unable to speak for themselves, and waiting to be saved, by a kind, white foreigner.

In her remarkably lucid and instructive talk, Adichie traces the development of this "single story" of disparate peoples, from its roots in Western literature to its ongoing perpetuation in contemporary mass media. She describes succumbing herself to the temptation of viewing people through a single-story lens while traveling in Mexico, and she also offers the following strategy, an effective way of countering the common perception of people like herself as "Africans":

I recently spoke at a university where a student told me that it was such a shame that Nigerian men were physical abusers like the father character in my novel. I told him that I had just read a novel called American Psycho — and that it was such a shame that young Americans were serial murderers.

Now, obviously I said this in a fit of mild irritation. It would never have occurred to me to think that just because I had read a novel in which a character was a serial killer that he was somehow representative of all Americans. And now, this is not because I am a better person than that student, but, because of America’s cultural and economic power, I had many stories of America. I had read Tyler and Updike and Steinbeck and Gaitskill. I did not have a single story of America.

Aside from expressing my gratitude for Chimamanda Adichie's highlighting of the problems brought about by "the danger of a single story," and illustrating its effects so well (and also expressing my gratitude to Restructure! for posting Adichie's talk on her blog, along with the transcript), all I can add here is, if you have a few minutes, please watch her talk and listen carefully.

Let's reject this "single story." We can do that in part by no longer referring to people as "Africans," unless they happen to do so themselves, and by paying closer attention to the intricate, beautiful diversity within any group of seemingly homogeneous people. The rewards for doing so are many, and our illegitimate presumptions of superiority will be kept in check.